Ties and handkerchiefs from Shibumi Berlin

2January 23, 2016 by Ville Raivio

Niels The Notorious and Benedikt The Benedetto from Shibumi sent me a tie and ‘chief to hear my thoughts on the make. I had seen the Italian-made accessories online but hadn’t handled them before, and was interested to see what they offer. To learn more about the company and owners, please have a look at their old Keikari interview.

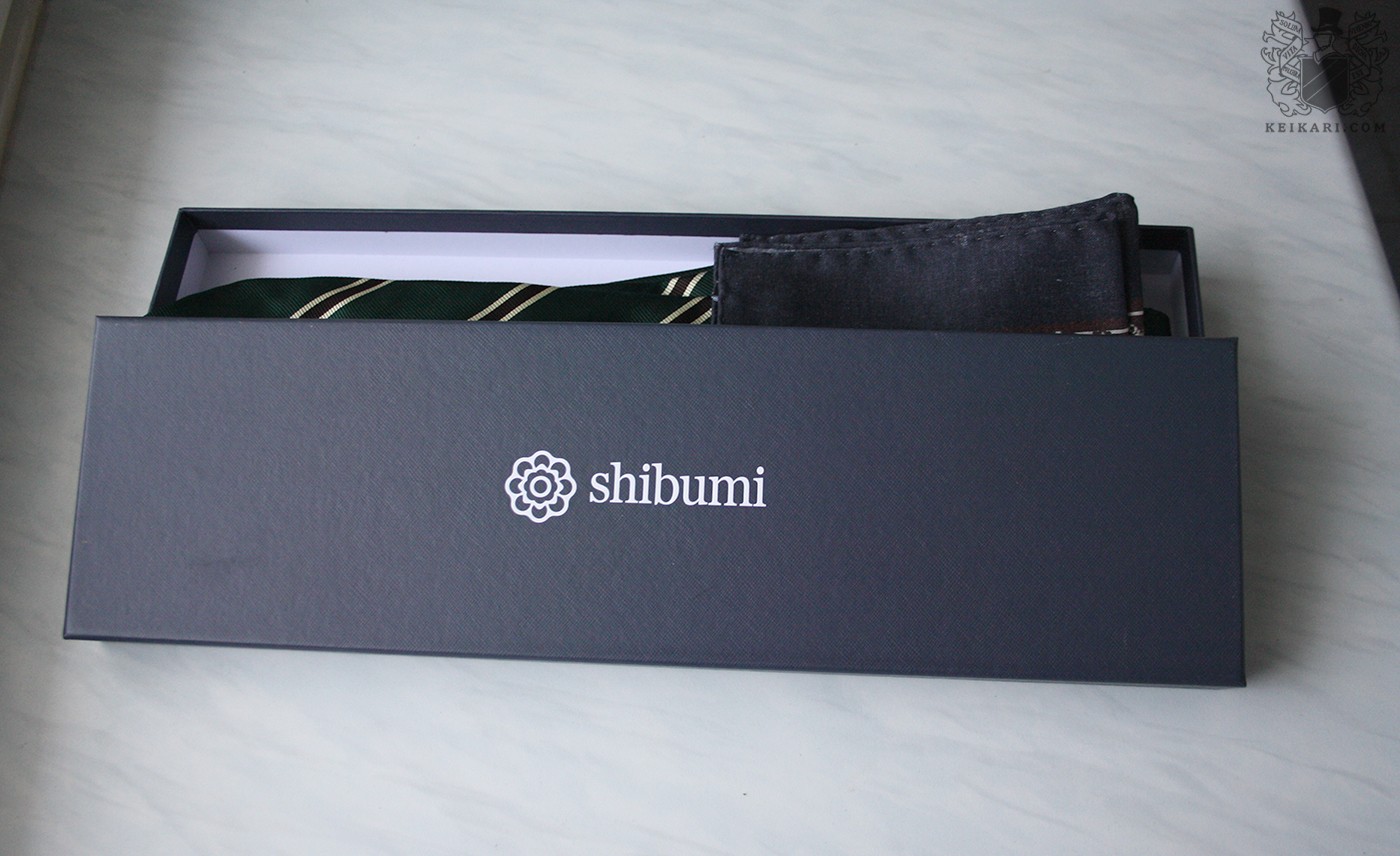

The handkerchief is a true Macclesfield print, made in the English city that gave birth and its name to a printing style. An extra large-scale paisley with navy, brown, cream and light blue colours, the piece is on the smaller side of ‘kerchiefs at 30×30 cm. I’m partial to this sizing as the Rubinacciesque blowout accessories make any breast pocket billow and gape in pain. The 70% wool/30% silk mix feels as dry as bones and does not wrinkle. While the edges are nicely and tightly hand rolled, the size of individual stitching is not yet on par with the likes of Vanda or Simonnot-Godard. The weave is very open but not a see-through show when laid next to cloth.

The tie is on surface a regular workhorse, repp weave with a regimental stripe and slip stitch, a combination of dark green, cream and brown. While the make is 3-fold with a hand-rolled point, the lining is a thicker double wool piece. Digging deeper, the material is indeed what Shibumi calls a super-repp: the weft does not show through. The silk is not as shiny as many repps are. The company offers their ties in two widths, 8 or 9 cm, with a 150 cm default length. A personal touch that enamours me is the flower stitch at the lower and higher part of the blade back. The hand-rolled edges are flatter than those on the handkerchief.

Looking at their store selection and the make of these samples, I feel Shibumi’s pieces are well-made. There are thousands upon thousands of accessory companies all around, and setting a new one apart from the others has become difficult, especially so as most of them do not own production facilities. Shibumi seems to have chosen the route of surprising materials (Solaro, alpaca grenadine, Fresco wool) or colours like neon coral and electric blue along with artisanal make, and those lovely flowery stitches. The lineup is growing and I hope they keep doing things differently, as done so far, for many years to come.

Category Accessories, Neckwear, Web stores

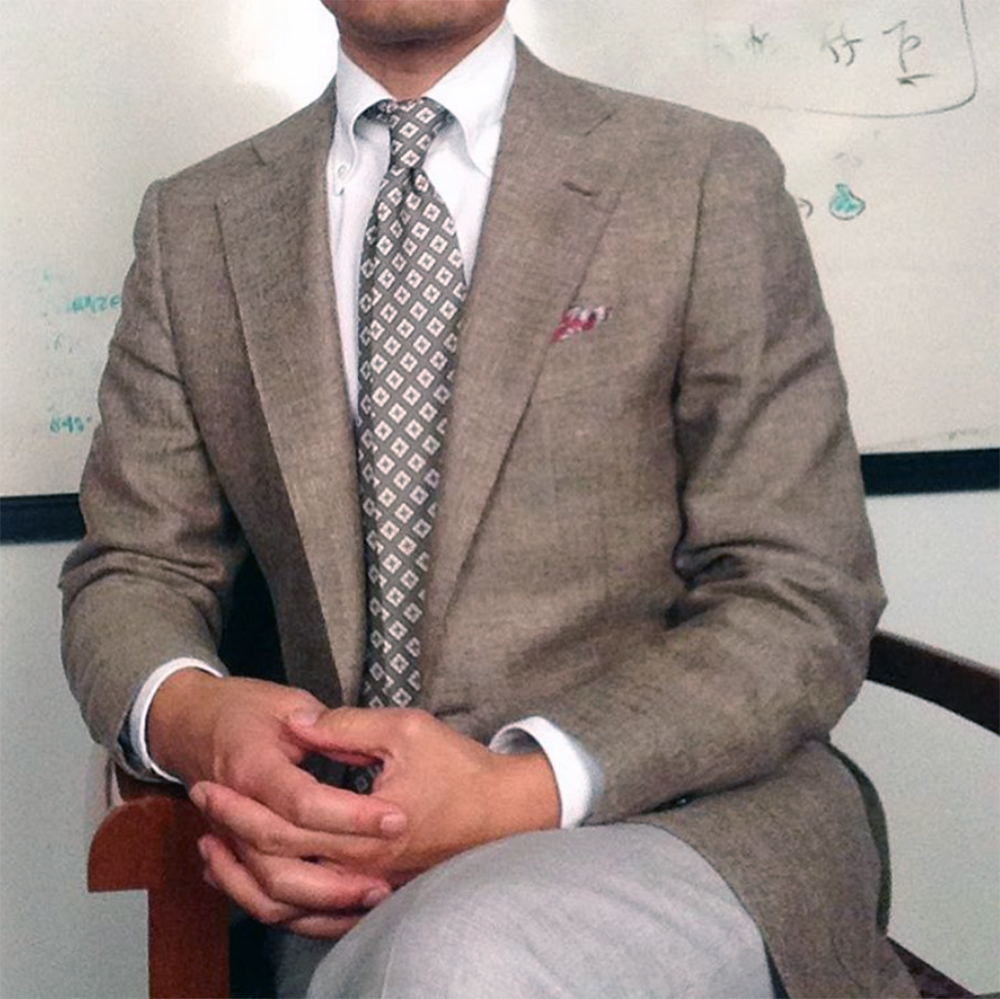

Interview with “TweedyProf”

0January 21, 2016 by Ville Raivio

Vr: Your age and occupation?

TP: I’m 45. I am a faculty member at a major research university in the US working on the mind and brain from a theoretical perspective.

Vr: Your educational background?

TP: I studied chemistry and biology as an undergraduate, and have a master’s degree and PhD from the University of California, Berkeley.

VR: Have you any children or spouse (and how do they relate to your clothing enthusiasm)?

TP: My family largely tolerates my interest. My wife generally likes that I am well dressed, but she probably thinks I own too many things and obsess about it. My two kids range from being positive (the youngest) to alarm and embarrassment (the teenager).

VR :…and your parents and siblings’ reactions back when you were younger?

TP: I grew up in an evangelical household, so a conservative one. Back in the 80s I aspired to what I suppose now might be called goth: lots of black, Doc Martens, and hair you wouldn’t want to expose to open flames. You can imagine my parent’s reaction. Tailored clothing was something I found much later in life. I’m sure my parents like that aspect of me better now. My younger brother shares some of the same interests though more focused on shoes. He’s recently discovered Vass, but then again, he doesn’t have kids.

VR: What other hobbies or passions do you have besides classic apparel?

TP: I’m a parent!

I try to play classical piano seriously though work and economics have made it difficult to take lessons which I think is essential to keep up one’s technique. I’m also quite fond of traveling, and we’ve lived in Berlin on and off for the past five years, and traveled around Europe quite a bit. There’s just so little time to do as much as one wants.

VR: How did you first become interested in style, and when did you turn your eyes towards the classics? Why these instead of fashion?

TP: My interest was born about four years ago from a practical problem that many Western faculty members face as university education becomes more like a service industry: How to maintain formality in a informal world?

I mean “formality” as a value, a sense of seriousness and decorum. Formality has an important place in life and certainly in academia. Its loss hinders education.

Here’s an egregious example of what I mean by “the loss of formality”: student emails. I’ve had one too many emails that began with “Hey [first name]” or at one point “Dude, where’s the final?” All propriety had gone to hell—though when tuition is $50,000 a year at many US private universities, that changes how people act.

I won’t expand on why I think this is a problem (hopefully it’s obvious). But how do you respond? I toyed with the idea of going “John Houseman” on my students (from the movie, The Paper Chase), addressing students as “Mr. X” or “Ms. Y” to reintroduce the formality of the student-teacher relation, but that just didn’t feel natural.

Well, then, at least I could look like a proper professor. In that context, “classic menswear” seemed like the right direction. My Styleforum moniker, “Tweedyprof”, when I joined in 2012 was tongue in cheek since I wasn’t that tweedy. It signaled an aspiration.

For me “fashion,” as I’m understanding it (what’s seen on the runway) would not achieve the effect I wanted, to reinforce the seriousness of education, of the classroom context, of having a professor as mentor and not a potential drinking buddy. That said, I do admire those who have a great fashion sense.

VR: How have you gathered your knowledge of the tailored look — from books, talks with salesmen or somewhere else?

TP: The beauty of a coat and tie is that it is both liberating and principled. Liberating in its uniformity (It’s a uniform!). But it’s constrained and organized by articulable principles and that’s what I enjoy about proper dress. You have to learn these principles, but once you do, a lot of freedom opens up.

Learning the basic principles isn’t hard. It isn’t rocket science. But it does require an eye for detail, a willingness to think a bit, and good mentors. I tried reading a few books but they didn’t do so much for me and I don’t think I ever finished one. I’ve never read Flusser’s Dressing the Man, what everyone suggests as a starting place. I’m sure it’s useful.

I learned a lot initially from Put this On, but most of what I’ve learned has been through interactions at Styleforum and I think when you are starting out in the English speaking world, it is a great resource. For me, it began with lurking, then posting a few pictures of a MTM shirt and MTM jacket I had done, getting some initial feedback that helped me learn where to look and what to look for. After that, really just following certain threads and observing “fits” from certain members, how they put together a look.

Lots of people influenced me and I can’t name them all so I hope I will be forgiven for omitting many teachers and Forum friends. I have to say, I was and continue to be greatly inspired by the Scandinavian contingent who consistently hit the highs (e.g. members EFV and Pingson, another academic who posts no more, alas, but can be found on Tumblr).

Manton’s good taste thread was often a revelation in the early pages and watching In Stitches progress was eye opening (you should see his early entries in that thread and contrast those with the pictures you’ve posted of him here, a transition that took no more than a year). The thread chronicling Gazman and MaoMao’s bespoke Italian adventures was intimidating and inspiring.

On the side, I’ve talked with Mr. Six, Claghorn, Cezinho, Sprout2 and Sacafotos among others about aspects of tailoring, especially ties. In NYC, I’ve run into folks like Greg Lellouche and Mike Kuhle who have been generous with their time and chatted with me. I also started the Classic Menswear Lounge thread where I hoped to generate more theoretical discussion, though the thread is quiet now that I don’t frequent Styleforum as much. Many of the participants in that thread were important in refining my sense of classic menswear. I’m sure I’m forgetting many people (apologies again).

VR: Have you any particular style or cut philosophy behind your own clothing?

TP: The most basic things is fit. One has to learn how things should properly fit, on others, but also on the body one has. You can read about fit, I suppose, but learning to see it is crucial. I wouldn’t call it a philosophy or style, but a necessity.

After that: details!

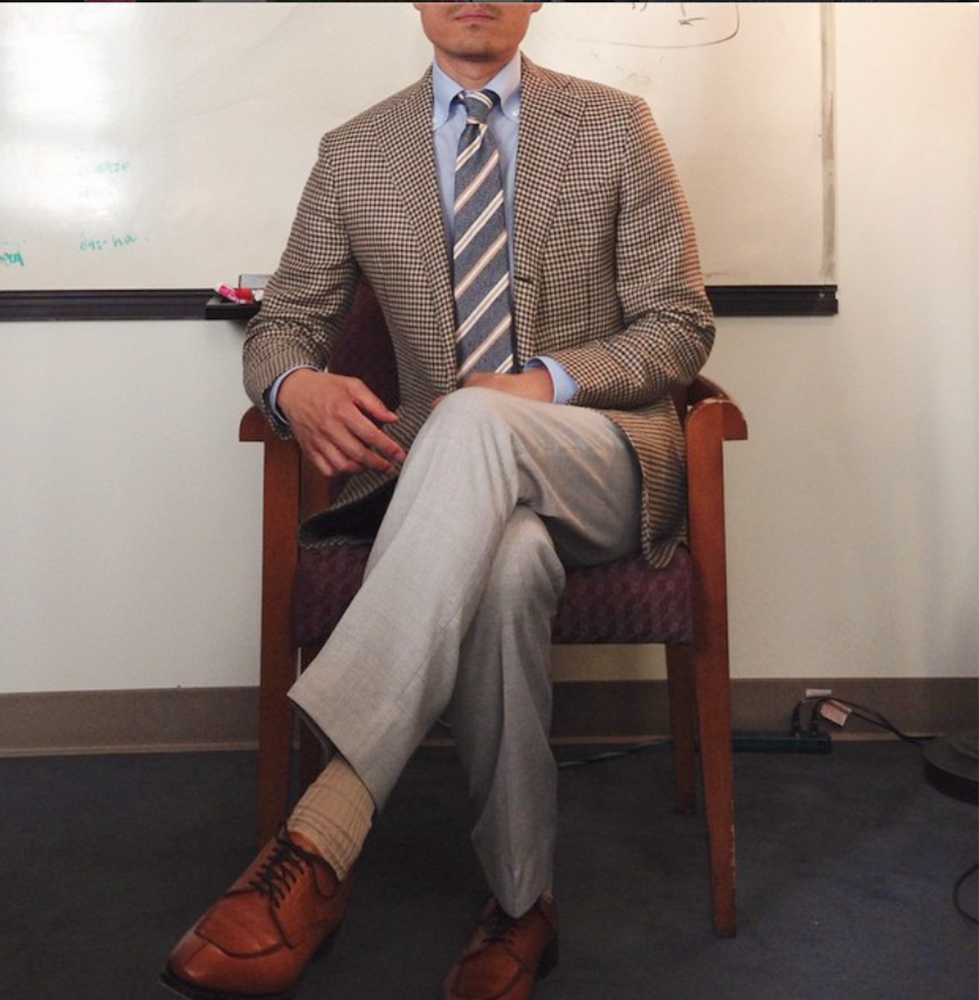

On myself for jackets, I prefer what I suppose might be salient aspects of a Neapolitan cut: broader lapel and more natural shoulder. Alas, I have bumpy shoulders so a soft shoulder is difficult to achieve since I do need some padding to smooth out the bumps. This balance is hard to find in ready to wear jackets though I’ve had good luck with Eidos Napoli.

I don’t wear suits, so having proper odd jacket details is important to me: larger scale patterns and patch pockets. These days, I gravitate more towards the solid end of the spectrum, so donegal or herringbone, something that provides visual detail but resolves to a solid in the distance.

On pants, I prefer a fuller cut, but I don’t cuff. I would prefer to cuff, but having bowed legs, I find a cuff tends to look cluttered given the way the trousers drape at the ankle for me. I’m sure a master bespoke trouser tailor could help, but that’s not in the cards, at least not until the kids graduate from college.

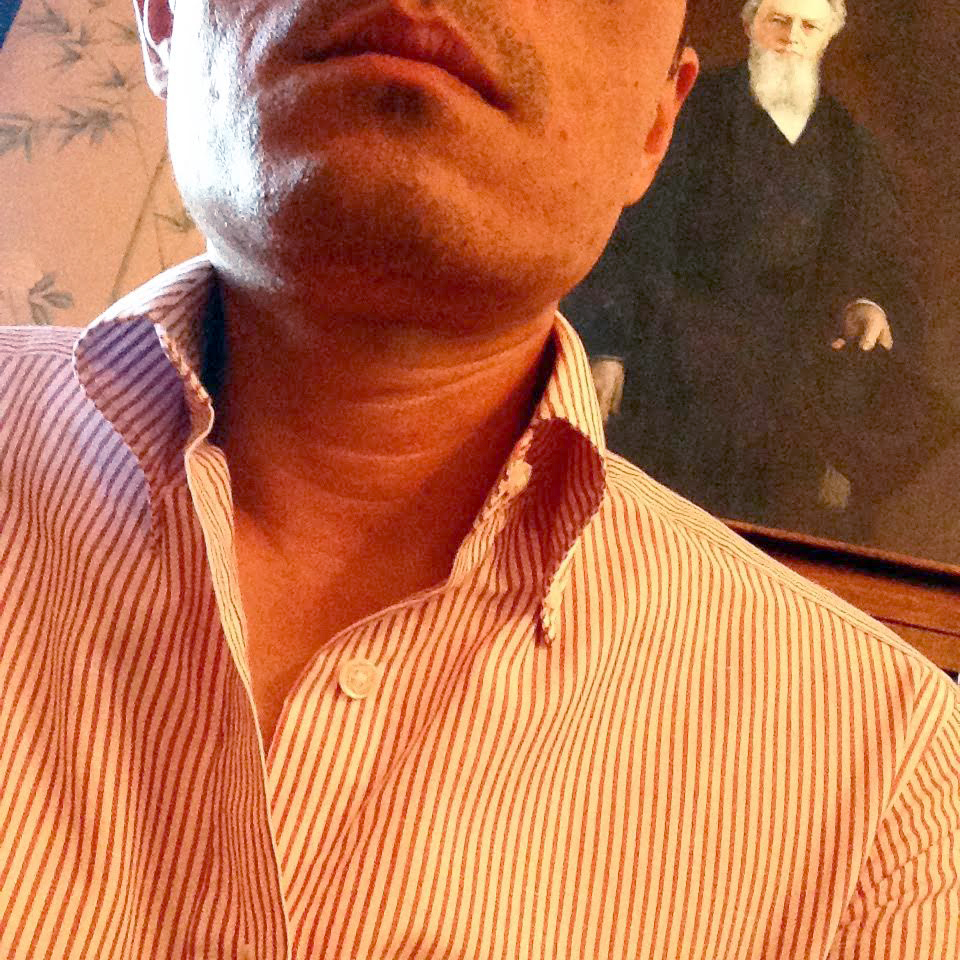

The shirt collar is something that one should attend to carefully but often gets short shrift. The most beautiful tie will be diminished by a crappy collar. I’m a bit obsessive about details here: proper (higher) collar height for my longer neck, soft, unfused points that aren’t too spread (again, to wear with odd jackets) but which roll softly under the jacket’s lapel, and small tie space. For button down shirts, the same features with emphasis on a unique and soft collar roll. I’m still tweaking with my shirts with the maker.

Ties should be well cut so as to knot well and be proportional to one’s collar, torso and jacket (e.g. lapel width). Materials should be seasonally appropriate.

Finally, accessories and matching them matter a lot to me, and with a smaller wardrobe, they provide the field for originality built on a firm foundation of fit. I’ve many thoughts on this, but I won’t bore you with the details.

VR: Who or what inspires you?

TP: I don’t have a specific historical figure who inspires me. Much of my inspiration comes from Instagram these days. As I said, the Scandinavian contingent provides a constant reminder of why good tailoring and fit are so crucial (you know who you are!). I also receive much inspiration from the Styleforum colleagues who I mentioned before and who are on Instagram. I tend to follow fewer people mostly because time is precious, and it’s hard to scroll efficiently if you have 100+ people you follow.

Mostly, I’m looking for inspiration, for the use of pattern, texture, and color in unique and tasteful ways, within the bounds of classic principles.

VR: What’s your definition of style?

TP: I don’t know if one should try to define “style”. You might as well define “consciousness”!

Maybe I can say what I try to do: to find my own place within the space of possibilities that are defined by the “principles” of classic menswear.

There are many places to be free in that space, and looking for your own place is what allows for originality and style. For classic menswear, the most pleasing originality to me is subtle, say finding a way to use a pocket square that both picks up certain elements of a tie but also generates an interesting contrast with it, all while harmonizing with other elements in a look, say the pattern of a jacket, the material of the shoes. Such a fit looks pleasing at a glance but to a trained eye also reveals a skilled play on color, pattern and/or texture.

Subtlety of this sort is often lost on social media where all we spare is a glance. I think it’s wonderful that some men present strident flair and ostentatiousness (think of very loud ties or exploding pocket squares). Why shouldn’t one enjoy one’s clothing? For me, though, I dress for work so the formal and classical are more crucial and originality must be subtler. That doesn’t stop me from enjoying clothes, of course.

VR: You’ve worked in the American academia for many years. How would you describe the most common outfits for men within the many hallowed halls?

TP: I think the thought in America nowadays is that one should be comfortable but where this means informal. “Informal” then means casual, sometimes to an extreme. This might make me sound too stodgy, but I’m sorry, a professor in shorts and t-shirt teaching a class is an abomination (unless you’re teaching hands-on surfing). Indeed, it’s just disrespectful to the students and to the context. A computer science professor I know once asked me why I “dressed up” for work, to which I responded along the lines of above, to reintroduce some formality to the teaching context. He added: “Oh, so you respect your students.”

Fortunately, the abomination I mentioned is uncommon (maybe more common in California). More typical among men are jeans or khakis and a button down shirt. Ties are really rare in the universities I’ve been at unless you are an administrator. More likely, you’ll have someone with a jacket, sans tie, over an OCBD and khakis or jeans.

Does this make the ivory tower grim style-wise? I suppose if by “style” one includes fit and formality, then perhaps yes. A clean fitting shirt and nicely cut trouser does wonders for such a look, but so often, men don’t pay attention to this. I like the modern academic uniform, but it’s casual, what I wear on weekends. It is not proper work wear for the ivory tower.

That said, I’m of two minds here. I value proper dress in the classroom context. I think a coat and tie are important for male faculty.

But then again, academia is hard, especially at the research level. Faculty positions are difficult to come by and achieved after years of hard work where you pretty much ignore everything else. Once you get your job, and many do not find one or only after years of looking, the pressures are doubled-down and teaching is secondary to doing good research. Many people have families too. So, it becomes an extravagance to focus on clothes.

Indeed, I’m very cognizant that in some way, my dressing up puts me at a disadvantage: it has the danger of making me appear frivolous to my colleagues. At this time in most American universities, classical menswear calls attention to itself. It is no longer mundane but stands out, especially if properly tailored and well cut to one’s body. Oddly, it’s inadvertent peacocking. So, while I think dressing properly, more formally, is important for professors, I’m not sure I would recommend to a junior colleague that they go my route. Or if they did, perhaps I would at least steer them away from the pocket square.

VR: Has the stereotypical tweeded professor lived on widely, or has he been driven into small pockets on the East Coast?

TP: I think the stereotypical tweedy professor is a myth or a dying breed. I do have a colleague in physics who wears tweed jackets and a bowtie. He looks good—a scientist no less!—but he is not the norm.

That said, there will be variation across universities. I suspect the northeast, with its seasonal changes, might allow for more variety of dress and, possibly, be the last protected lands for the mythical creature of which we speak.

VR: Is it possible to combine a passion for tailoring with academic credibility in the 2010s, or does shabbiness indeed guarantee authenticity and earnestness?

TP: I think it depends on the field. As I said, I think my dress can actually be a disadvantage, but I work around scientists and engineers for the most part. At this point, I’m tenured and have a body of work people feel is worth taking shots at (which is good; you want to be a target), so this protects me a bit.

Even among humanities faculty, I still stand out though as we move to the humanities and the arts, dress somehow is more tied up with one’s work or the persona that one perhaps cultivates more in those contexts. The drama professors have every reason to look great, though I don’t see them around much so can’t say for sure.

Remember, dress for me concerns aiding teaching, how I present myself to students. For research, it is much less important and as I said, possibly distracting and detrimental. I would much rather have someone come out of one of my talks saying, “He dressed like shit, but wow, what a mind!” than the other way around. Still, I suppose I aspire to “What a mind and what a jacket!”—in that order.

Ok, that’s too boring. My advice to young male faculty? Wear a coat and tie when you are teaching, and if asked by a senior colleague why you are “so dressed up”, just say that you are teaching and that you want to remind students that learning is serious business. You can slowly transition to wearing a coat/tie all week (“Oh, I have office hours” or “There’s a committee meeting”).

Wear a well fitting navy blazer with mid grey or mid brown trousers, to provide contrast with the blazer (not charcoal trousers or dark brown/taupe). A nicely tapered mid-brown blucher or oxford with some broguing, something not aggressively tapered but with a nice line (not too rounded of a toe). For ties: a near solid tie (for spring/summer, a tussah brown silk tie provides enough contrast and texture for an odd jacket), or a subtle herringbone. A good collar on blue oxford cloth for the shirt will finish off the look. Forgo the pocket square initially perhaps, or if you do, then a puff fold with squares that are subtle in color and pattern. You might be surprised that your students appreciate it.

Category Interviews, Men of style, Styleforum

A history of pyjamas

0January 19, 2016 by Ville Raivio

Pyjamas were originally loose, thin trousers that staid up with the help of a thin cord. Men and women shrouded themselves with these in India, Iran, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The trousers were usually paired with a knee-length tunic, the likes of which are worn as part of the shalwar kameez of today. The pyjama name comes from the Hindi word pair pae jama or pai jama, which mean leg clothing. The common use of pyjamas in Western countries began in the 1900s, but their history dates back to the influences of the British Empire and all the way to the 1600s. Europeans traversed to far-flung countries took them upon themselves as leisure wear, better suited to the climate of Eastern places than the woven woollens of the North.

Those returning to mother countries brought pyjamas with them during the 1870s at the least, as these were quite rare markers of status and globe trotting in Europe. Pyjamas made up of a shirt with trousers also covered lewdly hairy lower limbs more effectively than the previously popular long nightshirt. This garment, today so comically-looking, did hold back the tide of pyjamas until the 1920s as it was considered warmer in poorly insulated houses. Before the 20th century, at the last, the word pyjamas meant a set of nightwear, both the shirt and trousers. The exotic aura of pyjamas was quickly snuffed out as clothing factories smelled a moneyd novelty, and began making them in great numbers and marketed the garments as modern apparel.

In the 1910s, French fashion houses manufactured pyjamas for daywear as well as sleeping, and their extreme lightness influenced the make of other garments. In a peculiar league of their own were evening pyjamas worn by city madams for informal house suppers. The common cut of men and women’s clothes in the 1920s was narrow, almost genderless, and the era retained the favour of the Tens for pyjamas of many kinds. While men’s nightwear was usually made from cotton or flannel and undecorated, those for women were made from thin, smooth silks and viscose, dressed with lace and embroidery. The male pyjama was very colourful in the ’20s, perhaps to lighten the mood after the dark daywear. The materials and details of pyjamas varied for over half a century until the wild 1970s arrived. The manufacture of unisex pyjama models that began then has stayed with us.

The top of a classic men’s pyjama resembles a collared shirt, but its collar is often round and entirely soft, with cuffed sleeves. The body of the shirt often has a placket to frame the larger buttons. By far the most common cut is loose to make for comfortable sleeping, while a common touch is a contrasting, colourful piping. A breast pocket is the thing to add as most pyjamas have no other pockets. The original drawstring trouser waist is usually replaced with an elastic band. As for materials, woven cottons are durable and smooth on the skin, while plain jerseys stretch like no other, and both of these are defaults. While silks have been more common before, dry-cleaning them is a nuisance and the material wears hot and flimsy. Linen remains the coolest for summer, flannel the warmest for winter, and pyjamas can be varied endlessly with different materials and detailing. A more stylish garment for sleeping has not been invented yet, so pyjamas remain on man’s shoulders still.

Category Accessories

David Mitchell’s black tie style soapbox rant

0January 10, 2016 by Ville Raivio

Category Formalwear, Videos

Interview with Tomasz Miler from Miler Spirits and Style

0January 1, 2016 by Ville Raivio

VR: Your age and occupation?

TM: I am 31. I own SpiritsAndStyle, a company of 30 people that is focused on bespoke and RTW-clothes as well as selling whisky and large tasting events. We do all of that in any order you like :) We have a beautiful shop in Poznań and we also sell online at ShopMiler. I also have three blogs that in Poland attract approximately 250.000 unique users monthly and just now I’ve started a blog in English at TomMiler.

So, in few words, I sport a nice suit to tell people how to drink whisky, and then I put it all online to sell it with the help of my team.

VR: Your educational background?

TM: Master’s Degree in biotechnology (molecular diagnostics — I know, it’s weird), postgraduate studies in conference interpreting and a postgraduate course in business communication.

VR: Have you any children or spouse (and how do they relate to your tailoring enthusiasm)?

TM: I have been happily married to the beautiful Olga for over a year now. We have no children yet. Since we own a tailoring workshop we have easy access to tailors. The only problem involving my wife and tailoring I ever encounter is her being able to convince the staff to finish her blazer before my winter coat because “it’s not so cold yet so how could he mind that?” I guess this describes her attitude towards tailoring quite descriptively.

VR: …and your parents and siblings’ reactions back when you were younger?

TM: Real men wear suits. My father wears one as well. I don’t see any reason why this should cause any special reaction. But before the “tailoring era” I used to pump iron a lot. My friends from the gym were looking weird at me when I came there wearing a tie or a suit. But when you start lifting heavy iron people stop laughing :)

VR: What other hobbies or passions do you have besides classic apparel?

TM: I obviously live the two of my biggest passions: whisky and clothes or clothes and whisky (or even both at the same time ;) Other than that I like to travel with my wife (my fav destinations are Scotland and the US, and hers is Italy), I fell in love with sailing this year and I am thinking of getting a yachtsman’s certificate, I’ve trained in kickboxing and BJJ for a couple of years, I did a few half marathons and even a marathon, and obviously I am addicted to books. I also truly like to speak English. Oh yes, and I smoke cigars.

VR: How did you first become interested in style, and when did you turn your eyes towards the classics? Why these instead of fashion?

TM: I always feel that my story is not very poetic. When I worked out at the gym my shirt collar size was 47 cm and I had no belly. This meant that I couldn’t really buy anything in a RTW shop. It wouldn’t matter a lot to me at that time, but when I started to work as an interpreter (I mainly did simultaneous) I had to attend numerous conferences and business meetings where sporting a suit was obligatory. My teacher, Witold Skowroński, who worked for people like George Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Queen Elizabeth II and Lech Wałęsa truly inspired me with the bespoke clothes he was wearing, but more importantly he did something that few men would have ever done: he gave me the phone number of his tailor. Of course at that time it was a considerable expense for me, but look where it got me! And they say that clothes don’t make the man ;)

And when it comes to fashion, well, I haven’t really thought about it. There is some degree of fashion in classic elegance. The lapels are getting wider, braces are becoming more popular, the three-piece is coming back, the DB already is back. So there is some fashion in it. I don’t really care so much about clothes as you may think. I appreciate a guy who’s tattooed head to toes sporting a cool pair of sneakers properly matched with nice streetwear more than yet again another wannabe dandy checking hundreds of times per hour if his tie hangs down properly and whether his pocket square attracts enough attention. It’s the person inside the clothes that counts.

VR: How have you gathered your knowledge of the tailored look from books, talks with salesmen or somewhere else?

TM: I would say that for me this process developed in two stages. Stage one was when I read a lot to understand different nuances of tailoring and I also started my bespoke adventure in real life. The suits I would get were not quite like the ones I saw in my books and on the Internet so I started to negotiate with tailors on a lot of modifications. Some of them were successful and some were not (to say the least). I do have some truly unacceptable suits in my wardrobe but being persistent finally got me to the place where I know what I like. I quickly understood that your clothes should stem from two things: your body type and your personality. If you manage to match these two, you are good to go.

I thought I was advanced already but yet the second stage of understanding clothes came to me when I opened my tailoring workshop. I suddenly had to gain the ability to work on various body types and understand the very different needs of my customers. This made me really humble. Every day I learn something new about both clothes and people.

VR: When did you decide to set up your own tailoring store, and what goals did you set for yourself in the beginning?

TM:

To be honest with you, I had no master plan. Sometimes I was working as someone you could call a “bespoke assistant” through my Polish blog. Unfortunately, very soon I realised that when I work with tailors I am not superior in terms of working relations, they opt for solutions that in their opinion are more suitable, so I cannot fully implement what I envision. At the same time I was gaining on popularity in Poland as an expert on elegant style. I had more and more people asking me about suits and I thought I would try to employ a tailor. It was hard and we had to spend countless hours on discussing details of our work, but now we have a lot of orders and our tailoring team already consists of five people.

VR: Have you any particular style or cut philosophy behind your own clothing?

TM: Yes, my jackets need to be able to hold at least two bottles of malt whisky in their pockets. Just kidding! I already mentioned that I feel clothes should match your body type and personality. It is clear to me that when I look into the mirror, I don’t see a slim model with a six pack. I am rather short (175cm), have massive arms, got some belly too. I am no good for extremely tight jackets and narrow pants. It would be cool if I could wear them, as it is much, much easier to gain attention on social media when you wear clothes people recognise and like. But this doesn’t work for me so I had to find a different way and I try to surprise my followers with what I do. I also try to sprinkle it all with what I like in real life; a cigar here, a dram of whisky there and a lot of Harris Tweed. That’s it! Oh, and I have to say that I am crazy about vintage British fabrics and I am lucky to have dozens of metres in my private stock.

VR: Who or what inspires you?

TM: Some parts of my mind are academic. I like solid knowledge behind what I do. For instance, I read a lot about the theory of colours and I think that it is starting to work for me. I am also inspired by tradition and certain messages encrypted in clothes: a power suit at a business meeting, country clothes when on holidays, morning dress for weddings, tux at the opera. I like that. It would also be a lie if I said I don’t like classic Hollywood stars like Cary Grant, Fred Astaire or Clark Gable. And of course I keep my eyes open on social media. I also go to Pitti Uomo but I do it mainly to meet friends and business partners.

VR: What’s your definition of style?

TM: I think I can go along with the style definition of Hardy Amies whose witty writing I adore:

“A man should look as if he has bought his clothes with intelligence, put them on with care and then forgotten all about them.” I know it’s a bit of a cliché when you quote this again, but that’s just so true. If the clothes make you look like you think about them, for whatever reason, you don’t look good.

VR: Finally, during the last few years, I have noticed many style bloggers, companies and even a bespoke social club setting up new ventures in Poland. Could you perhaps explain why classic clothing interests so many Polish men?

TM: Well, I don’t know about so many, but indeed you could name a few that count. Of course there is also the BWB Bespoke Social Club that is one of the ventures that started it all in Poland. I am proud to be a founding member of this organisation. I have now changed my status from an “individual member” to a “supporting company” and I hope it will keep developing like it did over the last years.

I think that the reason why so many Poles are interested in style is very simple. For nearly 50 years the communist regime was depriving us of the possibility to express ourselves. In 1989, it was overthrown and we suddenly regained access to the western culture we used to be part of. After the initial period of getting it all wrong, we are already done with Adidas tracksuits and huge Versace logos across our chests. A lot of Polish men start to think whether they want their tie a garza grossa or garza fina grenadine or maybe shantung. And Poland is a very nice country too. Our big cities are very European and, having been a EU Member State for over ten years, now we no longer feel like we need to imitate only. We can create as well.

Category Bloggers, Interviews, Men of style, Tradesmen, Web stores

Copyright © 2013 Ville Raivio