Interview with Frank Shattuck

3May 29, 2018 by Ville Raivio

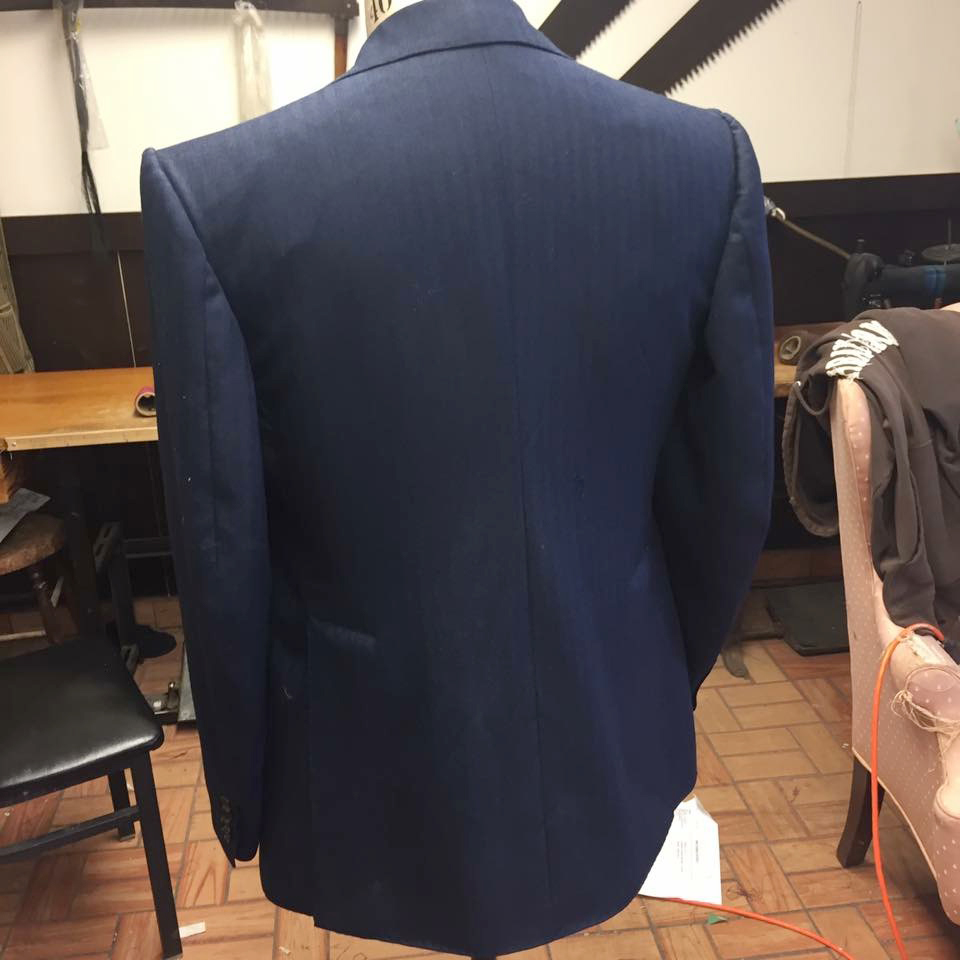

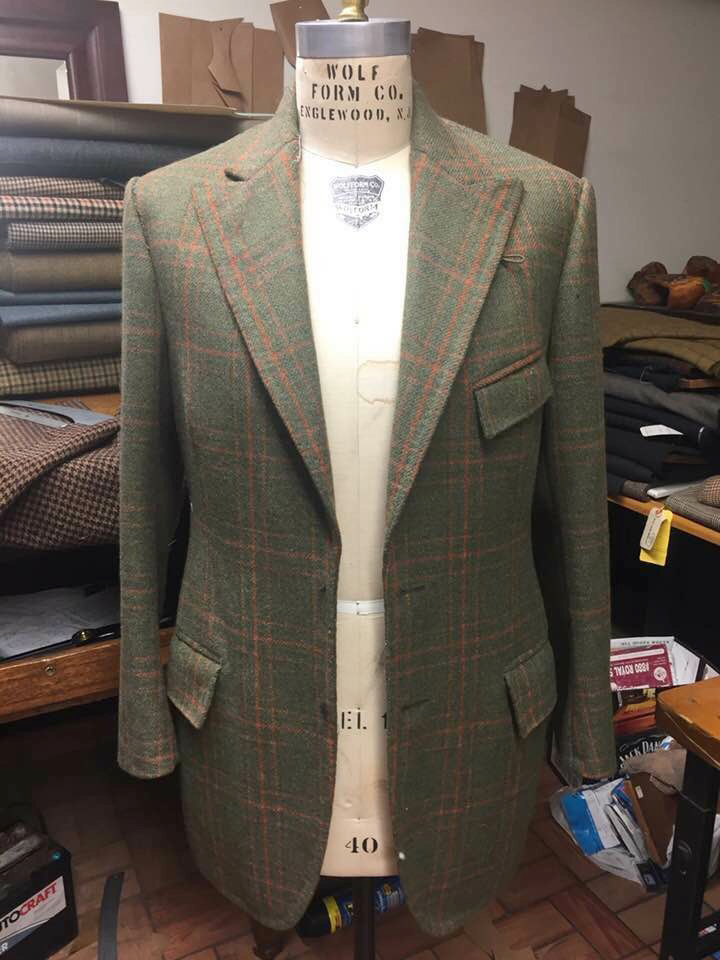

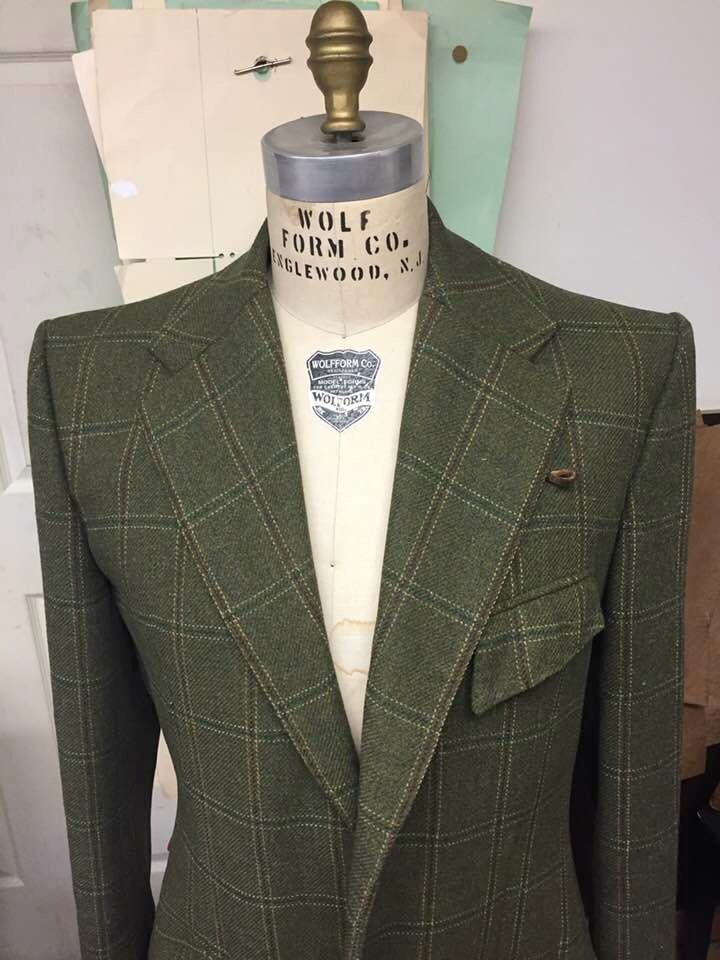

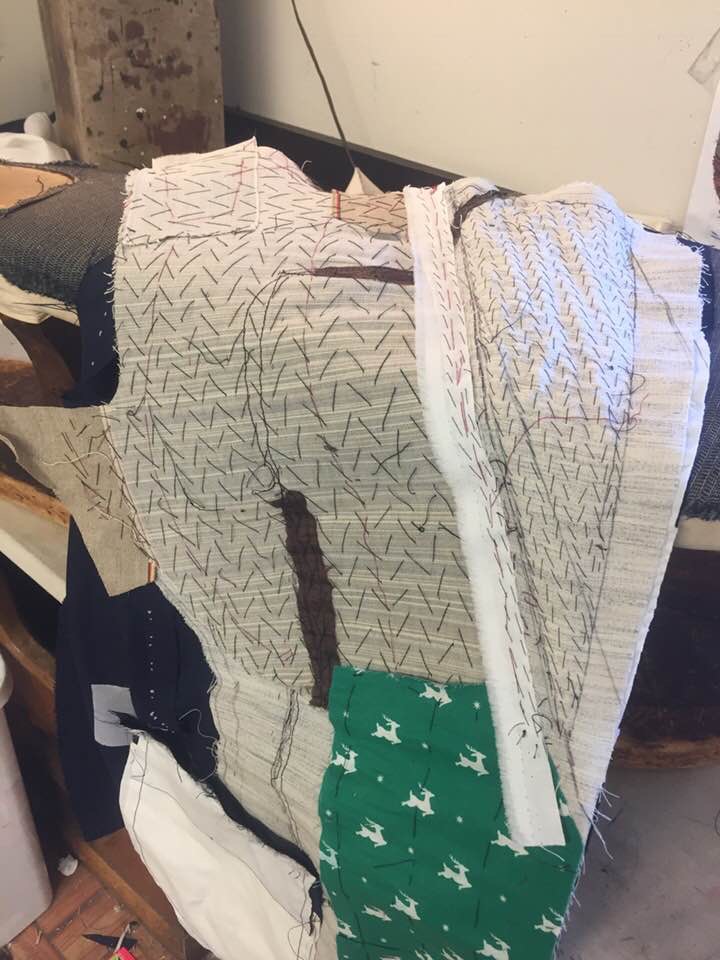

I became a tailor because it is a craft. I have always worked with my hands. Tailoring is an old, forgotten craft. An ancient craft. I started tailoring in 1982 with the Cesta Bros, Frank and Carlo, in their dimly lit shop in downtown Syracuse, New York, when it was still a fine town. My great grandfather’s patterns were still in the shop. They taught me old world ways. Hand work. Fitting. Pattern manipulation. When they retired I moved to NYC to continue my learning. And that I certainly did. I landed with The Great Raphael Raffealli, who took me under his wings and taught me old old secrets. Toninno “the genius” Christophoro worked for Raphael and took a liking to me, and took time to teach. He worked seven days a week and so did I. Sunday was the day he dedicated only to my learning. They liked me because they loved to laugh and I was a hilarious Irishman. We had a grand time for years. They taught me with love. I know of no other tailor today who knows how to apply a facing by hand. It takes eight hours. It’s the only way I do it.

I did a stint with the cantankerous but masterful master Henry Stewart. I learned from him his version The Mitchell System of drafting. He himself had many more secrets than in the book. I was a sponge full of roiling interest and desire to learn all old world methods. All and only. And I did. My hands also learned to know cloth. Good cloth. As only an old tailor can know because he works with it. All of the old cloths are gone. X bought the old houses — H.Lesser, Harrison’s and so on and he ruined them all. I’d love to tighten his neck tie for him. I did not open my first shop until 1997. 15 years after I started. I’d still be working and learning from the old men if they were around.

I use vintage cloths for my customers. Cloths worthy of old world ways. When old tailors retired I would buy out their stock. So I have a good store of old cloth. I also have access to a basement full of old thornproof tweed somewhere in Scotland. Ant there are two books I use today for suiting. When I find old blue book H. Lesser I buy it. The blue book are before X bought them out. Old cloths are higher twist. The yarns are twisted tighter. This makes for a “dry” hard, durable cloth that drapes and wrinkles not. Old cloth could easily last for years and years and then be handed down. Not in today’s throwaway world. Get an MTM with crap cloth and toss it in a year. Even the H. Lesser 7-1/2oz draped like a brick. Cloths today wrinkle and pill. Good old cloth is, to me, like rich topsoil to a farmer.

I do all [the cutting, sewing, making] myself because the finished coat is MY pride. MY life is in it. Like a bee makes honey I make suits. I am what I do. I have no house style that I have ever thought about. My style is what happens. How to make a functional suit along with the lines to make my customer an elegant man. I use the customers structure along with the given lines in my drafts, and I make him a pattern. I use forgotten pattern manipulation. All suits are pleasant surprises for us both.

What inspires me is an enthusiastic respectful customer and me making his trust in me pay off for him. I also get inspiration in telling disrespectful customers to go to hell. My definition of style is a well fitted suit, with no style purposefully added, worn by a confident man. I wish more people would realize the the new skinny suit style looks like PeeWee Herman, especially on overweight middle-aged men. I have stumbled upon the most amazing thing. I now do Skype fittings all over the world. I just finished a stunning suit for a gentleman in London using Skype. He likes it better than his Row tailor’s suit. And it is better. Pattern making is lost. I am also making for a gentleman in Finland. And it’s picking up steam. People want old world ways and hand work. and the feel of a well-fitted, tailored suit. I always have room for new clients. I love it when a new customer goes through the authentic fitting process and they realize that they are part of the suit too. And the feel what a coat and trousers should feel like. I love when, for the first time, they can sit down in their trousers and be comfortable.

https://www.instagram.com/thefrankshattuck/

Category Interviews, Tailors

The Art & Sole of Silvano Lattanzi

0May 25, 2018 by Ville Raivio

Back in 2010, the American Express Platinum card’s complimentary magazine Departures published a little something. The documentarist Jo Durden-Smith placed an order for a bespoke pair of Silvano Lattanzi shoes, and wrote about the ordeal, the company, and the artisan.

Art & Sole

The handmade shoes of Silvano Lattanzi display unparalleled craftsmanship and a singular aesthetic

By Jo Durden-Smith

The first thing that you notice about 49-year-old Silvano Lattanzi is his hands. Powerful and gnarled, they seem to belong to someone other than the immaculately suited man who greets me outside his shop on Rome’s Via Bocca di Leone. It’s the feast of the Epiphany, and the whole of the city seems to be out on parade in the late-morning sunshine, browsing through the windows along nearby Via Condotti and then gathering in groups like actors at a full-costume rehearsal debating (with the curtain still up) where to have lunch. Lattanzi ushers me inside through a decorated wrought-iron gate and introduces me to his current manager, Cecilia, a young Frenchwoman, who gallantly insists that she has had to come in to the small shop today “for a stocktaking.”

Lattanzi only has time to tell me, quite matter-of-factly, that he left school at the age of 14 before the telephone rings and he is called away. So I turn aside to inspect his shoes, although I don’t know quite where to begin. For there are astonishing numbers of thematics, far more than at any other bench-shoemaker I’ve ever visited. They’re in small glass-fronted lockers along the one wall, in the windows, laid out on every available surface; they compose a series of contemporary meditations on the classic designs of the 20th century ”the full brogue, the half-brogue, the country shoe, the loafer” in calf, suede, and cordovan: some exquisitely light; others much heavier, with a double-welt, a midsole, and two rows of decorative bottom-stitching. The patterning, the shape, and the curves of handsewn detailing differ from pair to pair; there are variations in color, in patina, and burnish. These are the shoes not just of someone who has already foreseen every conceivable demand a custom-client might make of him, but of an experimenter, a man who is restlessly working his way through all the possibilities (for personal statement, for fashion) of traditional forms.

It’s this restlessness ”this constant need to get on, to do more” that’s the second thing you notice about Silvano Lattanzi. In the end we spend a couple of hours in his shop, talking about his career: the long road that’s taken him from his apprenticeship to the heights of Rome and Milan, where he has an outlet on Via Montenapoleone. But I soon sense that this elegantly laid-out store is not his natural environment, and that he’s quietly uneasy talking about himself. He only seems happy, in fact, when he’s involved in something practical, like bending low to measure me for the pair of shoes I’ve come to order, or explaining the intricacies, shoe in hand, of the double-welt or of reversing the fiendishly complex process, forgotten now by many English custom-shoemakers, in which the upper part of the shoe is sewn inside-out and then reversed so that the stitching is barely evident. It’s only when he speaks about his work that he becomes both personal and, in a simple, self-effacing way, almost lyrical.

“I produce about 50 new models a year,” Lattanzi says, “and I take inspiration wherever I can find it, from nature, from my travels. It’s important for me when I travel to see beautiful places, beautiful women, museums, fine carpets, and fine palaces, because I want to reach out to that whole world and absorb it into what I do. It’s also important that I meet through my work men of intelligence and culture. When I go to the United States I like to take photographs of my custom-clients there, so I can remember and respect them. Without that memory, that respect, the soul goes out of the work: It does not come out well.”

Later, over lunch at a nearby wine-bar, he adds: “Passion is another basic element in what I’m trying to do. You know, people don’t appreciate what it takes to make shoes by hand. They don’t understand it’s physically tough work: dirty and exacting. They think that it’s automatic, repeatable, a sort of instant magic. But I’m there every day, side by side with my workers, discussing, comparing, experimenting and not only do we work very hard, we work with passion, we have to. We work with love. Hand-making must be perfect, absolutely perfect. You cannot do it if you are neurotic; you can’t do it if there are other things on your mind. You have to have a happy atmosphere and total, total commitment.” So it comes as no surprise to me when he announces as the meal ends: “You must come and see it for yourself!”

Soon after lunch, then, we jump into his Mercedes-Benz and spend the late afternoon driving across the spine of Italy, stopping only to gaze at a snow-capped mountain transformed into pink ice cream by the last flourish of the sun. And next morning, after a night in a hotel on the coast, I ring the front doorbell of the little balconied house on Via Mostrapiedi (literally Show-the-Feet Street) in the hamlet of Sant’Elpidio a Mare, about a half-hour drive from the Adriatic port of Ancona. I don’t exactly know what I’m expecting. A place with the same sort of methodical, meditative calm, I suppose, that I’ve found in the custom-shoemakers I have visited in London. But what I find, though driven by the same craft imperatives, could be on another planet. The front door opens onto a stairwell; off to the left is a tiny office that’s piled with papers and files; and beyond the office there’s a buzz, a whirl, a hubbub of activity. Fourteen or 15 people are crammed into a relatively small space, along with tables and racks of finished shoes, antiquated machinery, and an extraordinary contraption of movable, tiered metal baskets filled with lasted footwear of every color, which snakes up and down one side of the room. Near the door, in a space of their own, two seasoned old “bottomers” are sitting on low stools, calmly stitching on welts, the thin strips of leather which hold the “upper,” the lining, and the insole together. But everywhere else in the room workers, darting from station to station, variously pincer, staple, water, hammer, nail, and measure in what looks at first to me like organized chaos.

Lattanzi, who is now wearing a grubby white coat, introduces me to his workers and then says, “All right. Today, just to show you, we’re going to do something that we normally wouldn’t do: We’re going to make you a pair of shoes in only twenty-four hours!”

The tan leather town-shoe that I have chosen, a model called Barkin, combines utter simplicity, the minimum of sewn decoration with supreme elegance of form. Once more Lattanzi measures me, carefully turning my feet into two outlines and a series of figures. Then, with a set of pre-made patterns in hand, he leads me past the buffing machine and a group of “finishers” to the cutter’s, or “clicker’s,” bench.

What follows over the next few hours is a virtual master class in the art of shoe-making. While the clicker is busy selecting a skin, Lattanzi explains the fundamentals of hide preparation. For ordinary leather he uses the top layer, which has a grainy texture created by the animal’s pores and the bases of its hair follicles; the layer beneath it, made of collagen fibers, is napped into suede. Most of his calfskin, Lattanzi says, comes from England (“absolutely the best in Europe”), and the leather used to make the soles comes from Düsseldorf. Cordovan, which is made from horse muscle, comes from Chicago; ”crocodile, lizard, ostrich, and snakeskin we import from all over the world.”

The skin that the cutter finally brings down for my shoes is handed to Lattanzi who turns it over and pulls at it. “First, it has to be the right color, of course,” he says, “to take the particular coloration I’m after. But it must also have, in the parts that we use of it, a fine texture, a good grain. It must be elastic,” he says, stretching it again, “and it must have a uniformity of thickness. If the skin is too thin, I won’t use it at all.”

He nods at the cutter, who lays the patterns down on the skin one after another and cuts round them with his long “clicking” blade (the name comes from its sound), sometimes leaving space at the pattern edge and sometimes adding through the pattern what seem to be chalk guidelines for the stitcher. When he is done, he repeats the process with a thinner piece of leather for the lining, and then he hands the pile of cut shapes across his bench to a young woman sitting at a punch press below him.

Her first task, which she starts without pausing for breath, it seems, is to chamfer down the under-edges of some of the leather pieces, a process called skiving, “so that wherever they are put together for stitching there will be only a single thickness,” says Massimo Bizzocchi, Lattanzi’s American agent, who has joined us. Then she takes other sections and punches out a line of holes, the eyelets for the laces, and carefully fits metal rings in some of them. Finally she gathers together the pieces, puts them in a plastic bag, and takes them upstairs. Lapsed time so far: 35 minutes.

Bizzocchi and I follow her to a room overlooking a garden planted with lettuces, herbs, and arugula; farther down the hillside we can see the beginnings of the huge new workshop Lattanzi is building. For the next hour we watch as his sister, Fabiana, painstakingly assembles the incoherent pile of leather snippets into something that finally looks like a shoe. She goes downstairs once to replace a section spotted by wax from the candle she uses to burn off loose fibers. She twice unravels a whole section of stitching because she is not satisfied with the line. (“Silvano is a very tough critic,” Fabiana says.) But by the time she’s done we have a finished lining and upper, which resembles a shoe in the same way a face would if it were peeled off and laid down flat.

Downstairs, we introduce ourselves formally to Lattanzi’s mother, Delia, a quietly cheerful, bespectacled woman who is finishing off shoes for Jil Sander and Brioni (while outside, her husband, Angelo, hoes and weeds the garden). Lattanzi himself we find crouched on the floor whittling away with a piece of broken glass at a last, which he’s already built up at the sides with what looks like plaster. “No machine can do this,” he says, looking up at me. “Only hands, knowing where you want to add and where to take away.” What he’s been doing, he says, is creating the shape of my feet out of standard-size lasts. (Normally Lattanzi makes a custom last for each client.) He’s even added a bridgelike leather prosthesis, to represent my high arches. “There,” he says, standing, satisfied with his scraping. “Now we can begin.”

He briefly inspects the uppers for any sign of blemish. Then he splashes water on them and, using two different brushes, glues the uppers and liners together in preparation for the lasts. “Regular glue and mastic glue,” he announces. “The mastic dries quickly and becomes soft where you want it to be soft, while the regular glue takes longer to dry, so that you can manipulate the surface of the shoes on the last.” He puts temporary laces through the carefully aligned eyelets and ties them tight. Then, one after the other, using no more than pincers, a hammer, and nails, he forces the two upper-liner assemblages down onto the lasts.

It takes no more than a few minutes. But it is an extraordinary performance, a combination of strength and an absolute certainty of eye: strength, to pincer the leather smooth and tight round the last’s edges before nailing the fringes onto the base; and certainty of eye, to make sure that the alignment and symmetry of the shoes are not skewed in the process. When he’s finished Lattanzi compares the two covered lasts with a pair of calipers, and he finds that they match exactly. I feel like applauding his accuracy. He simply gives a small grunt of satisfaction, and then passes them on to one of his workers, who splashes water on them and then begins to hammer out the leather.

“This is the next stage,” Lattanzi says, standing over him, “the tapping in of the fibers, starting the process that is in the wear of the shoe. Water is very important here because leather is a living material. It absorbs water, and when it dries out, it will keep the shape that is being hammered into it. After this the shoes stay on the last for two more days, we’ll water and hammer them again, and then they’ll stay on the last, acquiring the memory of their shape, for another two to five weeks, depending on the humidity, the weather.”

As I’m led through the subsequent processes, the heat-flattening of the base of the shoe, the setting of the insole, and the interposition of the shank, which supports the foot’s arch, I begin to understand why the 4,000 pairs of shoes Lattanzi makes annually command such high prices, $3,000-$5,000 for the first pair (which includes the making of the last), and similar prices for subsequent ones, though selecting an exotic leather can make the cost even higher. And then I am led to the central mystery of custom shoemaking, the hand-sewing of the welt.

Most shoes made today don’t come with a welt but are instead held together by being cemented or injected with hot plastic. The welt, by contrast, is stitched onto, and through, upper, lining, and insole. But in Lattanzi’s hands, it becomes a sort of fugue. He is a virtuoso of the single welt; the double, which will be used for my shoes (with an extra midsole for strength); and even the triple, which when I get back to London is described to me by a custom shoemaker as “used only for rigid, waterproof ski-boots, and then not really worth the trouble.” And yet Lattanzi shows me women’s shoes of an extraordinary delicacy that are triple-welted. They are rigid, certainly, and as water-resistant as it’s possible to be, but with the platform of the shoe a showplace for a variety of intertwining, decorative cross-stitching.

When evening falls, it is time for my first fitting. Lattanzi searches out my shoes from the racked baskets, unlasts them, puts a temporary sole and heel on them, and then, when I’ve put them on, bends down to feel my feet through the leather. “The lacing isn’t quite right.” Then: “Too tight,” he announces. By the time I come back in the morning, on my way to the airport, both lasts have been changed; and a toepiece on one of the shoes, which had somewhere along the way been slightly discolored, has been replaced. The whole workshop now seems to be involved. Lattanzi is still not satisfied. He says that he’ll change the last once more, and that I’ll get my shoes, ”Perfect!”, in six weeks.

After I say goodbye to everyone, to Lattanzi’s mother, to his sister, to his father, who comes in from the garden, Lattanzi drives me to the airport. And I say to him that I’ve never seen a group of people work so hard together in my life. He’s pleased. Then he says to me: “You know, in 1981, which was the year of the birth of my son Paolo, I realized that I was broke; my company, Zintala, was going nowhere; and it was then that I was forced to grow up. I understood that the cemeteries were full of undiscovered geniuses, and that if I really wanted to succeed, I’d have to work. Ten years later I opened the shop in Rome.” And since then? “Whatever has happened to me, I think,” he says slowly, “I owe to other people: to my clients, to Cecilia, to Massimo Bizzocchi, to people like you.”

At the little Ancona airport Lattanzi buys me a coffee, and then we say goodbye, promising to meet again. Six weeks later, my shoes arrive. I unwrap them, take out the shoetrees, and put them on. They are like a second skin; and I finally realize the truth of something that all custom-shoemakers have always told me: “When you put on your first pair of bench-made shoes, you will never be able to wear anything else again.”

Category Footwear, Quality makers, Reading

Interview with Patrick Hall

0May 24, 2018 by Ville Raivio

VR: Your age and occupation?

PH: I am 35 years old, and an Episcopal/Anglican priest. I currently work as the Episcopal chaplain to Rice University in Houston, Texas, in the United States.

VR: Your educational background?

PH: I took a bachelor’s degree in history and philosophy from the University of Texas, and a Master of Divinity from the Virginia Theological Seminary.

VR: Have you any children or spouse (and how do they relate to your tailoring enthusiasm)?

PH: I have no children but have been married for two years to a wonderful woman who is something of an aesthete herself. She is almost as invested in my wardrobe as I am. She has endearing attachments to some of my clothes, and always mourns when the seasons change and seasonal pieces go into “hibernation.” We are mutually invested in each other’s delight with clothes. She also wears a fair bit of vintage clothing, and we are each other’s first opinion whenever we are thinking about buying things. I am really grateful for a spouse who is neither threatened by nor annoyed by my eccentric love of tailored clothes. My wife has a keen sense of taste that compliments and informs my own. I know that not everyone is so lucky.

VR: …and your parent’s and siblings’ reactions to style back in the days when you began?

PH: I am an only child, so I have never had to contend with the opinions of siblings. My parents are befuddled by aesthetics, and my love for the tailored wardrobe in particular. They epitomize the sentiments of many Americans who came of age in the 1960s. They regard tailored clothes with a vague disdain because the tailored wardrobe represents a political/economical/cultural milieu that the “baby-boom” generation rejected in favor of what G. Bruce Boyer calls “prole gear.” My father dutifully wore the American uniform of worsted suit/button-down shirt/repp tie to work for most of his career but seems never to have taken any joy in it whatsoever.

VR: What other hobbies or passions do you have besides apparel?

PH: I am also passionate about historic preservation. My hometown of Houston, where I still reside, is ritually sacrificed to the god of the wrecking ball every ten years. I believe history should obligate and constrain us, that we are made wiser when we are forced to grapple with edifices from the past, rather than always choosing the easy out of designing for an empty lot. I am part of a community of people here in Houston who give voice to the memory and taste of dead men, though our activism is often futile.

VR: How did you first become interested in clothing, and when did you turn your eyes towards the tailored look?

PH: I have two early memories of tailored clothes – wearing a morning suit as an attendant in a family wedding at a very young age, and dressing for church each week in a blazer and flannels. I was immediately enamored with the dignifying properties of tailored clothes and have unrepentantly preferred them as long as I can remember.

VR: How have you gathered your knowledge of clothing — from books, in-house training, workshops or somewhere else?

PH: This is a really important question, because most men suffer the results of the aforementioned mid-20th century rupture, where the knowledge of how to deploy the language of classic menswear was not inter-generationally communicated. My father could not explain the casual utility of patch pockets or demonstrate how a button-down collar was supposed to roll, or what kind of shoes to wear when. Furthermore, it is nearly impossible now to find salespeople or tailors in the United States who are trustworthy guides in classic menswear, unless you live in New York. So, like many of my peers, I have filled up what knowledge was lacking through the internet and books. Like many Americans, I am particularly indebted to Alan Flusser and G. Bruce Boyer, and vintage enthusiasts like Marc Chevalier, whose collective work has kept alive an American perspective on classic menswear that was in danger of being entirely lost on account of widespread neglect.

VR: How would you describe your own dress?

PH: I wear a personal uniform, in that my embrace of classic menswear is total. I have built my wardrobe to be entirely interchangeable, and I wear all my clothes in rotation, with the exception of ties and pocket squares and socks which are chosen intentionally to harmonize all the other randomly sequenced pieces. I like to juxtapose colors and patterns. My hope is that my compositions toe the line between good taste and dandyish narcissism. I also mix vintage and modern pieces, as a way of critiquing the disposability of modern fashion. My hope is that my compositions also toe the line between good taste and period costume.

VR: Who or what inspires you?

PH: Old photographs offer a great deal of inspiration for me. I try to learn from the effortless way tailored clothing was worn by anonymous men before the ascendency of prole-gear made the entire language of classic menswear antique. I love the anonymous snapshots of men in tailored clothes that overflow baskets and bowls at antique shops. They are my teachers. I am also inspired by the taste of public figures both past and present who speak the language of classic menswear proficiently – Prince Charles, Gregory Peck, Tom Wolfe, Robert Lowell, Anthony Eden, Julian Bond, T.S. Eliot, George H. W. Bush, Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle, Jr., and so on.

VR: What’s your definition of style?

PH: As it relates to the wardrobe, style is an eye for clothes which suit one’s body and communicate an idiosyncratic sense of taste. Because style must be self-aware, it is always unique and particular. People with a sense of style may opt into fashion trends that suit their proportions and taste, but are not buffeted about by the endless, tacky churn of fashion brands. In this sense, style has a permanency to it.

VR: I see that you have a passion for vintage garments. Why take this extra mile when the shops are full of everything?

PH: Ah, would that the shops WERE full of everything. Economies of scale have not been kind to the tailored wardrobe. As a result, going vintage is one of the easiest ways to get garments of exceptional quality and faultless fit with unique detailing for less than the cost of bespoke. Furthermore, pre-1960 cloth is simultaneously more robust and more breathable than today’s, being heavier than modern cloth but less densely woven. This resulted in garments that endured more shaping by the iron, and tailors were able to offer their customers clothes with incredible shape – swelled chests and nipped waists that could be cut close at the button point without buckling under the tension like modern fabrics do. There were also a myriad of patterns and colors that are just not available today, because demand for tailored clothes is so much diminished. I have handled swatches of worsted wools from the 1920s with a depth and surface interest that dwarfs anything put out by today’s mills. Also, because a man might have two suits that saw daily wear for almost every circumstance, vintage clothes were designed to live and move in – invariably, my vintage pieces are the most wearable in my wardrobe. Finally, we all need to be thinking about sustainability in our lives. Wearing vintage clothes is an easy way to signal that we are reducing our reliance on disposable products that deplete natural resources during production and end up in landfills after just a few months or years of wear. Our cultural obsession with “newness” is a relatively recent fad and is doing our world no favors.

VR: Finally, given your ecclesiastic background, what do you feel we should know about dress in Christianity?

PH: This is a difficult question to answer, as Christians represent an unfathomable diversity of perspective, and are often appallingly bad at doing justice to our faith. But I believe that the Christian Gospel is a dignifying message, a story that makes human lives and human community more beautiful and more meaningful. Tailored clothes have a similar aim – every man will need something particular and unique from his wardrobe, depending on the specific idiosyncrasies of his physique. Tailored clothes broaden, they slim, they lengthen, they shorten, they draw attention to the face. In short, tailored clothes are designed to uniquely dignify each man who wears them. The tailored wardrobe is the raiment of western civility, and it disposes its wearers to their neighbors. Tailored clothes harmonize best with judicious kindness and respectful comportment. Christians have, at their best, always worked for just such a community, where every person is dignified through their relations with every other, and judicious kindness and principled respect are the celebrated. I wear tailored clothes to signal my respect for the public square and for the other people who I find there. It is my Christian faith that has fostered such respect in me.

Category American style, Men of style, Vintage

Copyright © 2013 Ville Raivio